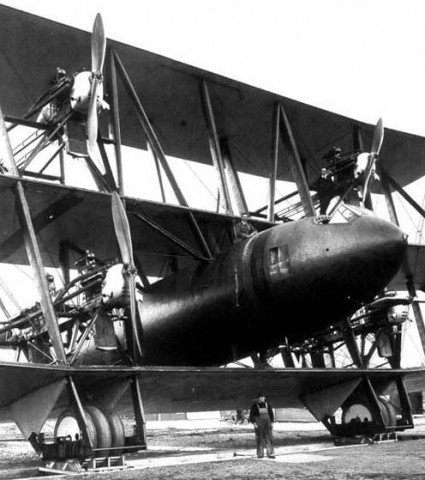

The Tarrant Tabor, a prototype bomber designed and built in 1918-9. There were high hopes among strategic bombing advocates (including P. R. C. Groves) for this giant machine, but by the time it was ready for its maiden flight in May 1919, the war was over and its purpose now unclear. Not that this mattered much, for that first flight was abortive:

The designer of the Tabor, Walter Barling, went to the United States where he designed the similar Barling Bomber a few years later. This didn't crash, but wasn't particularly successful either: it couldn't even overfly the Appalachians. It ended up disassembled in a corner of Wright Field.

All of that is just an excuse to post the picture of the Tabor and to point at the place where I found it, x planes, a tumblr blog devoted to striking aviation images. (The crash photo is from a Russian site.)

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Erik Lund

There's a great, if hair-raising article on the big planes in an early postwar volume of Jour.Roy.Aer.Soc., back when it was still the Aeronautical Society. (1923, I think, but don't hold me to it.) It lays out the structural safety factor compromises involved in building these planes. You _would not_ catch me going up on one of them, even if they were retrofitted with wheel brakes.

Chris Williams

IIRC, it was wheel resistance that was the problem, or rather, that when you opened up the Tabor's top four engines, it tipped up. It's a shame for a number of reasons, not least because had it worked, they might just have tried it with that steam engine originally intended for the Bristol Tramp, with excellent steampunk cool points ensuing.

JDK

Let's not forget that a couple of pilots were killed in that mess.

Barling is well covered in Gilbert's "The World's Worst Aircraft" - a great book of disasters.

Never mind the Tabor, have a look for the first 'Amerika Bomber' circa 1918, of which only one wheel survives in the hands of the IWM. That would be the Poll Giant Triplane. No photos or even drawing survive, so no one knows what it looked like...

Heath

Great. I'm trying to cut down the number of blogs I follow, you know... :P

Erik Lund

At the time the Tabor was test "flown," they still hadn't figured out its centre of gravity. Which tells us something. My imagination was leaping ahead to the moment where they got various of these monsters into, more or less, the air. What happens if you have to abort ..and you have no wheel brakes?

"Don't worry, everybody, we'll come to rest eventually. Everyone just get comfy on a stack of bombs, and don't worry about that hedgerow...."

JDK

Tabor. c of g wasn't the issue (they didn't get that far) nor brakes. Thrust line of engines was far too high, and combined with a boggy airfield and injudicious use of the throttles did for the pilots.

The emphasis on wheel brakes misses the point. Aircraft of this era had a brake - it was the tailskid at the back. For take off, getting the tail up was crucial, which 'released the brake' if you like. For landing, the aircraft would arrive for a three point landing, just above the stall, at max (still flying) drag. Airfields were grass, and round, and aircraft landed into wind. Wheel brakes when they came in on 1930s taildraggers were a mixed blessing, aiding steering on the ground at low speeds, but otherwise ineffectual at higher speeds (it's not a wheel-driven - or retarded - vehicle remember) and usually a good way to tip the aircraft on its nose at lower speeds. Good airmanship involved NOT needing to use brakes, using flight control and drag for manoeuvring and slowing respectively. The change to Bristol Blenheims from Hawker Harts was where the cultural and technical change in skill caught a lot of pilots in the RAF out - prior to that, brakes weren't crucial except on the few surfaced runways. (What happens if you have to abort? Put the tail down close the throttles and the skid and drag will slow it faster than cramming on wheel brakes would.)

It's a variation on the myth about the aircraft on a conveyor belt never being able to get flying speed - it's the wings, not the wheels that matter.

In today's airliners reverse thrust is more important than wheel brakes for stopping on the runway (but nosewheel toothpick machines are a whole different, lesser form of flying, of course.).

PS: Besler Steam plane or Clement Adler Eole III for real, successful and semi-successful steampunk points.

Erik Lund

JDK -good points. The thing about the giants, though, is that they're just so much bigger than anything ever flown before. Runway lengths and obstructions were already serious issues in 1918. There wasn't enough run to abort a Vimy with complete safety in some places, never mind these monsters.

It was not the single most pressing technical issue (see below), but it was the most salient one as a policy issue. With the end of the war and the expiry of the Emergency Act, the RAF lost many airfields overnight virtually overnight. There was literally not space nor room for these planes in Britain anymore; and the fit of air strength to airfields is the issue that James famously singled out as the single most important missing factor in the story of the rearmanent of the 1930s.

As I suggested, when I mention air brakes, they're proxies for a whole range of technical problems that confronted designers who were scaling up without giving any thought to --well, anything, really. I mean, they were still working on _cable controls_ in 1918, for Heaven's sake! Some of the big 'planes of the 20s and 30s had tunnels out to the engines so that someone could crawl out to adjust the idle screw by hand.

I could (obviously) go on: flap actuators, undercarriage shocks, cockpit instruments, fuel pumps, just off the top of my head. Although if we're going to fix on a single snag, it would have to be the low safety load factors identified so long ago. (Or enginer reiliability.) The problem with that, though, is that you can get away with low reliability and a 2.5 load factor if you're lucky, and some people are going to write about these things on the assumption that you just will be lucky --like the guys who wanted to send up a shuttle on the day after Challenger exploded just to show the universe that we weren't chicken.

The point here is that the Giants of 1918 were about as technically plausible as the "online shopping malls" of 1999, a moment of irrational exuberance in the technical Zeitgeist.

JDK

Are we off topic yet?

The 'Giants' of the 1910s were a chimera, really, but the one issue that really mattered for all aviation was engine power and reliability. Most of the issues you've mentioned had been addressed by people who had come up with ideas - have a look at the brakes on the FE2a and Sopwith 1&1/2 Strutter for instance; but they weren't of much actual use, and as weight was always the issue, they were taken out.

Big aircraft were viable - if the engines were there, but for other reasons they weren't a good idea. The Dornier DoX showed what could be done, soon after, while the Sikorsky Illya Momorets in the early 1910s - and in flight engine access was vital as the engines weren't reliable enough to be left alone - they weren't powerful enough to achieve real altitude. (Later, the Short Sunderland had in-flight engine accessory access, which did save some aircraft over the Bay of Biscay.)

But, as you say, building something that could be lifted by the engines of the day resulted in designs that were either draggy and (just) strong enough or structurally weak - where I do agree with you! However field numbers and sizes is a red herring. Most of them had ground runs that in today's terms would be regarded as STOL; they needed slightly bigger fields than the average farm's. They were big, ergo had a lot of mass, but they didn't go fast, so not much of a speed/distance factor/vector. Flaps (brakes etc.) weren't required for aircraft that landed 'three point' tail down until aircraft speeds increased significantly. (I'm curious as to what was the alternatives to cable operated controls in the 1920s.)

The Americans (DC-2, Boeing 247) and Germans (Junkers F-13 and Ju 52/3m) realised what a practical size aircraft would be and what to make it out of; metal. The British continued towards W.W.II with fabric covering or wooden aircraft - good in niches, but not the future of high load-factor aircraft.

Absolutely.

But otherwise I'm wary of the contempt of hindsight - many designers were working well and with innovation throughout the history of flight; and today's ease and efficiencies were built on the shoulders of these giants.

Erik Lund

Topic? There's a topic?

As I said, I picked wheel brakes as a synedoche for all of the components that had to be made betterer before 'planes as big as the Tabor would be practical. And I could have picked better. I think it's possible to underestimate the amount of trouble that a H.P. V/1500 would be in if it had to abort and land shortly after takeoff, but the 30,000lb plane trundling towards the hedgerow at 50--60mph would only be able to use its brakes to steer.

The reason that I wanted the synedoche, though, is to get at the point that the two decades 1919--39 were not wasted years. It's one thing to have an idea, whether it be wheel brakes, a metal-clad monoplane, or a control cable so sensitive and reliable that a pilot could use it to adjust carburettor idle screws. It is quite another to actually develop it.

And that is why I reject the old historiography of 'WWI-DC1--WWII," in which the way forward is obvious, but the entire British industrial-strategic community is taking one long nap until the "Battle of Heligoland wakes it up. Interwar aviation development is a much more complicated and many-faceted process than that; one in which we have to take the Rolls-Royce Merlin's auxiliary device powershaft as being a development on par with, say, the aluminum cladding of the Douglas airliners.

Nor, as a matter of fact, were the Dougas airliners particularly good weightlifters. Where they shone was in high cruising speed, reflecting the different priorities of the air mail subsidies of the American versus European governments.

Brett Holman

Post authorNot off topic, to the extent there was a topic. But very interesting -- do carry on.

Heath:

The first step is admitting you have a problem!

Andrew B

Brett,

Just a quick one to say that I'm a huge fan of Airminded, so was most pleased when you mentioned my Tumblr site!

Basically, it's just a way of sorting my bookmarks visually, but with the added capability of other post types, tagging, finding other stuff within the Tumblr community etc.

THIS is a good way of browsing all the images..a couple of them are even - *gasp* - my own..

All the best,

AB

Brett Holman

Post authorNo worries, Andrew. They really are great pictures!